Move Over, Dear Diary

Lifebooks Come Alive as Part of the Third Grade Writing Curriculum

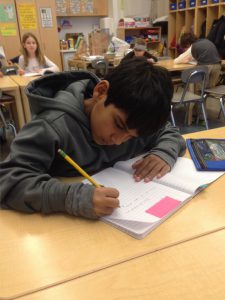

The third grade lifebooks start as simple black marbled notebooks, and the students’ first goal is to personalize them. They begin by collecting clippings to decorate the book’s covers in ways that reflect their personal interests; photos of New York, family members, and animals abound.

The blank pages inside are also gradually personalized, one thought at a time. “The book becomes a place to collect ideas,” explained Lower School Teacher Julia Smith. “The children are planting seeds to see which things they want to grow.”

The blank pages inside are also gradually personalized, one thought at a time. “The book becomes a place to collect ideas,” explained Lower School Teacher Julia Smith. “The children are planting seeds to see which things they want to grow.”

Take this (abbreviated) entry by one of the students on the topic of “Memories,” written in the form of a list: First time my brother is at camp; Acadia; Grampa dies; Learning about seals; Women’s world cup; Christmas in Charlottesville; My first bike. Everyone’s memories are unique, and each of them easily could form the basis of a longer, more descriptive, yet deeply personal story.

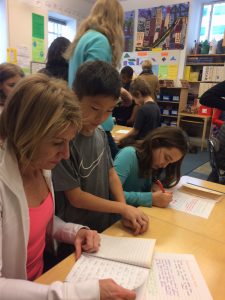

By the end of the first writing unit, Personal Narratives, the students have written and polished a written piece of work based on an entry in their lifebook. They bind each of their finished narratives and share their works with their classmates and parents at a morning “publishing party.”

Refine and Enhance

The lifebook has been a fixture of the BFS third grade curriculum for some time now; based on their own teaching experiences over the past several years, in which they refine and enhance their practices, Julia and her head teacher colleagues Sarah Gordon and David Bournas-Ney have made it a signature third grade program. One of the teachers’ inspirations is Ralph Fletcher’s A Writer’s Notebook, in which the author makes clear that such a book is not a diary or a class journal in which students are given precise assignments. Fletcher instead compares the notebook to a woodland ditch filled with fresh rainwater and colonies of growing creatures. “A writer’s notebook is like that ditch – an empty space you dig in your busy life, a space that will fill up with all sorts of fascinating little creatures. If you dig it they will come. You’ll be amazed by what you catch there.”

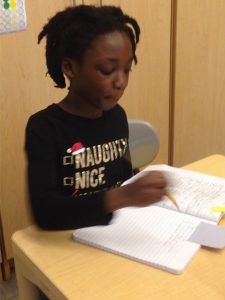

One of the benefits of the lifebooks curriculum is that it appeals to a range of writers at various levels in their skills development. “Lifebook writing allows reluctant writers the freedom to explore and be inspired by topics that truly interest them,” said 3B Head Teacher David. “It also creates differentiation in that each writer can experiment with the new techniques, language and ideas for which they feel ready.” In fact,

Now in her 12th year at Brooklyn Friends School, 3A Head Teacher Sarah takes a long view of the value of lifebooks. “When we hand children their lifebooks at the beginning of the year, I always tell my class that years from now they are going to be able to look back at their lifebooks and know all about who they were as eight and nine year olds,” she said. “They will see what memories were important to them, what they were learning about, what they were worried about, what they loved, what they imagined and what they thought about.”

Now in her 12th year at Brooklyn Friends School, 3A Head Teacher Sarah takes a long view of the value of lifebooks. “When we hand children their lifebooks at the beginning of the year, I always tell my class that years from now they are going to be able to look back at their lifebooks and know all about who they were as eight and nine year olds,” she said. “They will see what memories were important to them, what they were learning about, what they were worried about, what they loved, what they imagined and what they thought about.”

A Source of Inspiration

Children’s book author Julie Sternberg, whose daughters are now in high school, was so inspired by the lifebooks that her children kept in third grade that she was inspired to write a series of books based on the concept. The Top Secret Diary of Celie Valentine chapter books. Friendship Over and Secrets Out! were the first two in the The Top Secret Diary of Celie Valentine chapter books series. “I was the kind of kid who loved the idea of writing every day but was too lazy to put pen to paper,” she said. “I so wish now I had filled the pages of those lock-and-key diaries I begged my parents to buy instead of only the first few.””

Her regret-tinged nostalgia explains in part her appreciation for the lifebook project. “I thought it would result in a collection of writings that my daughters would end up treasuring,” she said. “And, in fact, it did. We all love everything about the lifebooks now.”

Julie initially envisioned the Celie Valentine series of books as a collection of lifebook-like journals in her protagonist’s life. She described her vision of “a collection of writings in a variety of formats – some journal entries, some responses to writing prompts – by a girl in a lower school.” In the end, in order to smooth out the narrative, Julie converted the books into a more straightforward diary format, with other kinds of writings taped inside the diary. “Regardless, she continued, “the BFS third grade lifebook project was absolutely a primary inspiration for the series.”

How It Works

How It Works

Lifebook homework involves daily writing exercises “to build up their muscles,” said teacher Julia, “both the graphomotor ones and their endurance for the writing process.” Students also read personal narratives written from young peoples’ perspectives, like How to Get Famous in Brooklyn by Amy Hest, in which an 8-year-old’s writer’s notebook is lost and scattered to the wind, making her a celebrity. “The book is very sensory in terms of the writer’s explorations of her neighborhood,” said Julia. “We then ask the kids to go off and write about a place they know well.”

As for their own personal narratives, the second stage is reflecting back over the contents of their lifebooks and finding an idea about which they wish to write in more depth. Students put careful thought into selecting which piece they will write about, spending a full month crafting and honing their narrative to share with an audience.

After planning, drafting, revising, and editing, students copy their finished personal narratives by hand into handcrafted books that are displayed in the classroom. Students read and comment on each others’ work, and parents are also invited in to view them. The lifebooks and their seed ideas will continue to accompany the students throughout the year’s writing units including fiction, poetry, and sometimes an intersection with the social studies curriculum.

Incubating Ideas

Lower School Curriculum Coordinator Diane Mackie is an ardent lifebook fan and advocate. “I like that it engages kids to write in a way that is individual and personal, that it’s a readily available avenue for kids to share thoughts, feelings, ideas, wonderings. Kids can run with it, walk with it, meander and ponder, as they choose.”

Like author Julie Sternberg, Diane’s own two children went through the program. “Some children fill two or more composition notebooks a year loving the opportunity to collect “seeds” for possible longer pieces or for future more developed stories or to document their lives,” she explained. “Others are not nearly as prolific and may just meet the requirement of four small pieces of writing a week. I had one of each child as a parent.”

Like author Julie Sternberg, Diane’s own two children went through the program. “Some children fill two or more composition notebooks a year loving the opportunity to collect “seeds” for possible longer pieces or for future more developed stories or to document their lives,” she explained. “Others are not nearly as prolific and may just meet the requirement of four small pieces of writing a week. I had one of each child as a parent.”

As with Julie’s daughters, and doubtless many others, Diane’s now-young adult children look back on their lifebooks with pride, she says. “They delight in the written record of their third grade year and reconnect to the spirit and soul of who they were or continue to be. It’s a lens into their 8-9 year old selves.”

Diane recalled a quote from the influential Fletcher: “A writer’s notebook is like an incubator: a protective place to keep your infant idea safe and warm, a place for it to grow while it is too young, too new, to survive on its own. In time you may decide to go back to that idea, add to it, change it, or combine it with another idea. In time the idea may grow stronger, strong enough to have other people look at it, strong enough to go out on its own.”

“The sense of ownership is something that really resonates with third graders, and they treat their lifebooks as treasured objects from the moment they receive them.” – Sarah Gordon