Lab Science in the Upper School: “Doing It Yourself and Seeing It Happen”

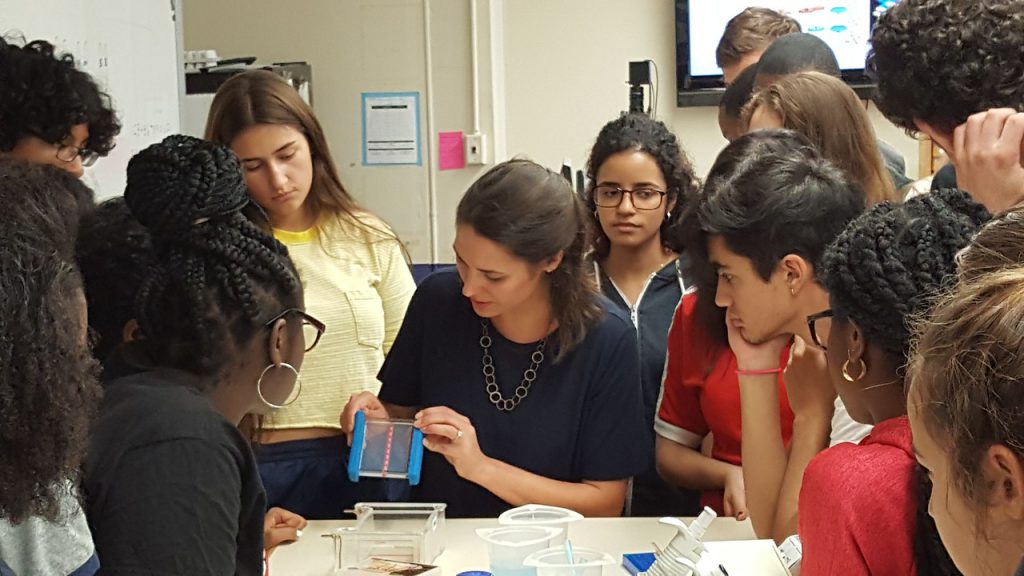

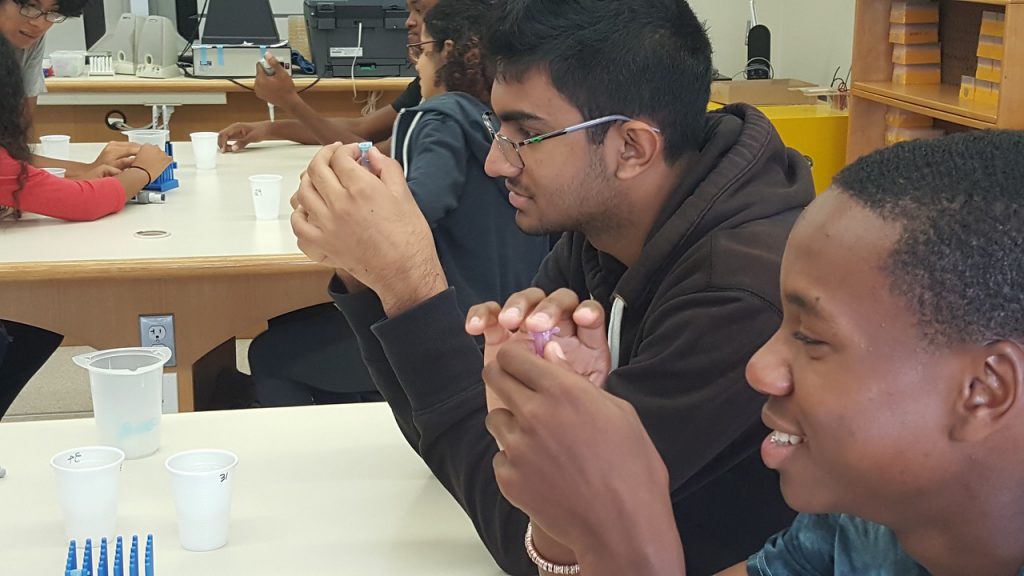

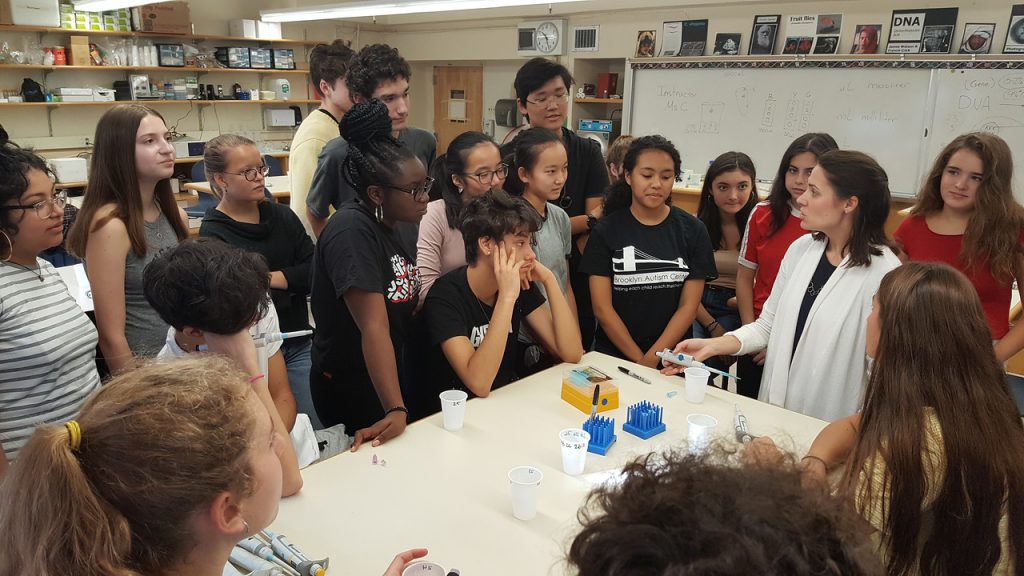

Sixty-four students in the IB Junior and Senior Biology classes, along with a class of seniors studying Forensic Science, recently took field trips to the Harlem DNA Lab to complete mandatory lab experiments in sequencing DNA and undertaking DNA forensics work. The Harlem facility is a collaborative effort of the New York City Department of Education and the DNA Learning Center (DNALC) at the famed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in Suffolk County, New York.

Upper School Science Head and Science Teacher Blake Sills explained the BFS students’ lab experiments. “They participated as investigators of their own DNA, which was collected from their loose cheek cells that are normally found in saliva. They performed several detailed protocols in their investigation, including amplifying the samples through polymerase chain reaction (PCR), then examining their own DNA for specific markers in non-coding portions of chromosome 16 by using gel electrophoresis techniques.”

The material was partially a hands-on review for the seniors and an introduction for the juniors. Besides learning the practicalities of lab work, the experiments served a larger curricular purpose. “Our human ancestors split into two groups for this marker approximately 60,000 years ago,” said Blake. “By the end of the day, students were able to determine if they possessed the heterozygous or homozygous condition for these markers, and consequently realized who in the group they were –more or less — related to through ancient DNA lineages.”

The Harlem DNA Lab draws on the DNALC’s long experience in translating current biological research into hands-on learning activities, according to the lab’s website. The lab was developed with more than $26 million in federal and foundation grants. Since its founding in 1988, the DNALC has provided experiments for over 574,000 students from the New York metro area during field trips, in-school instruction, and DNA summer camps.

“I’m not saying we’re all going to become scientists from one lab in 11th grade, but we can’t dismiss the possibility. This trip instilled in me a hunger to know more about my genealogy and my history.” – Amina W.

The off-site lab research experience was an excellent complement to the intensive laboratory work that takes place in the three fully-equipped science labs at Lawrence Street.

Ninth grade science studies begin with Biology, building on the concepts students learned and developed in the Middle School. “There’s a focus on project-based learning, working in small groups,” said Upper School Assistant Head of Academics Paul Beekmeyer.

“You’re learning by doing the project rather than the project being the assessment tool at the end of the learning period,” added IB Coordinator Pete Prince.

In tenth grade, students move on to Physical Science, with students choosing courses in either Chemistry or Chemistry/Physics. Eleventh and twelfth graders may choose from several different courses: IB Biology, IB Physics, IB Environmental Systems and Societies, or General Biology. Electives, such as the aforementioned Forensic Science, are also part of the program.

The Science Department has five faculty members: Department Head Blake Sills, Teresa Cano, Nicole Guynn, Lucien Kouassi, and Lyubov Obertnaya. Their course work with students is supported by Matt Pacicco, the behind-the-scenes expert on laboratory work in the Upper School. A graduate engineering student at NYU Tandon, Matt is now in his second year at BFS, working on a part-time basis.

On a recent school day, he was prepping a membrane lab for the eleventh grade IB Biology class. “We have elodea, which is an aquatic plant,” he explained. “When you put it in salt water, water in the plant’s cells exits through the cell membrane and the cells shrivel up in a process known as plasmolysis. You can see this effect when looking at elodea cells under a microscope.”

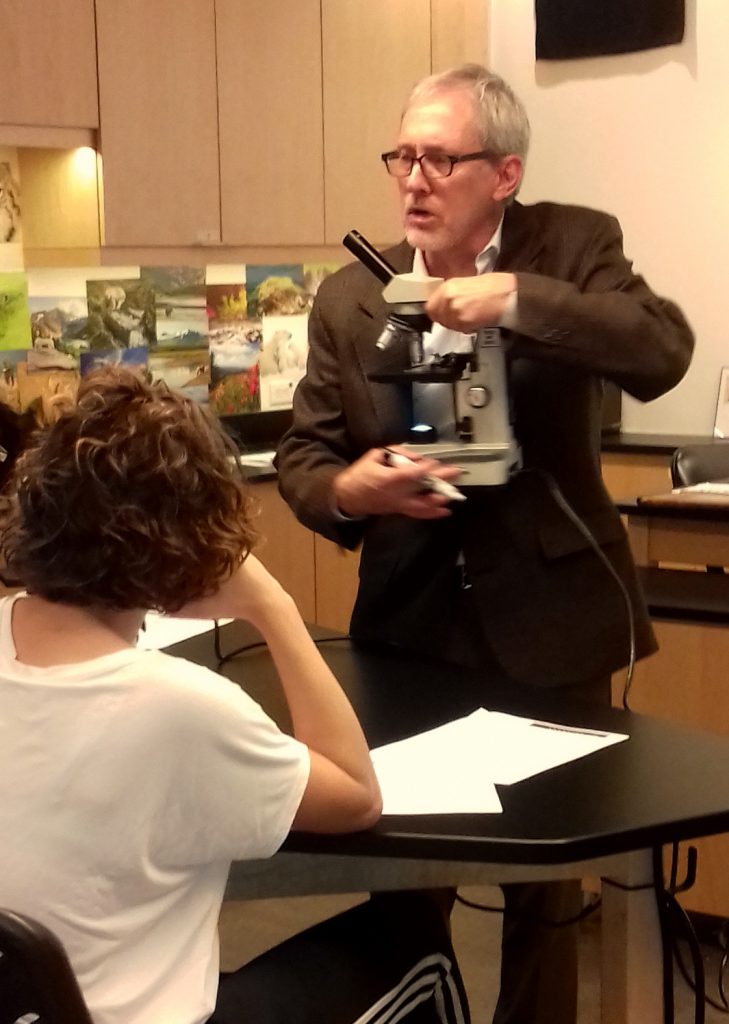

Science Teacher Blake Sills explaining the use and settings of a microscope

In the tenth grade Chemistry and Physics course, students will soon be performing flame tests. “They’ll take salt water made up of different combinations of salt compounds–and they burn differently; some will burn bright red, green, orange–and expose them to a flame,” said Matt. “By analyzing that, we can tell what the samples are made of. In the first round we give the students known samples so they can understand the process and see which compounds burn which colors,” he explained. “In the second round, they use their data and experiences from the first section to identify unknown compounds in the next group of samples.”

The tenth grade students most recently examined the densities of metals. “They’re given different samples of metal that can’t be measured with a ruler due to their unusual shape, so the students have to get creative,” said Matt. “First they weigh it. Next, they measure the water displacement by placing the metal in a graduated cylinder filled with H²O, and from those numbers they can calculate the density.” He stressed that the ability to perform such tests is useful in any scientific discipline, including environmental studies. “Density differences drive ocean currents all over the world. It’s like the old riddle, what weighs more, a pound of feathers or a pound of bricks?”

To wit, in the eleventh and twelfth grade IB Environmental Systems and Societies course, students recently studied ocean currents and the relationship between them and worldwide climates. “That’s why England can be at the same latitude as Canada but have the same climate as the Carolinas,” Matt explained. “Ocean currents are driven by differences in salinity levels at different depths. In the lab experiments to illustrate this, we used fresh water and had the students recreate the layers of salinity in ocean water in a graduated cylinder using different colors of salt water. The water with the most salt sank to the bottom. We then heated the cylinder and watched the layers merge together.” The lesson? “Ocean warming has the ability to modify the layers and thus global climate patterns.”

Matt Pacicco

Matt is in his final year of graduate work at New York University in Urban Infrastructure Systems with a concentration on water. “One upcoming lab will focus on local water quality issues including lead in drinking water and bacteria in our ecosystems.” He has held many laboratory jobs in his collegiate career, having double-majored in Chemical Engineering and Environmental Studies at the University of Rochester.

“I thought working in a school would be interesting,” he said of his applying for the lab tech position at BFS last year. “I’ve always had an interest in performing lab work as a way of teaching. It’s one thing to read about it in a book or have someone explain it to you, but there’s nothing quite like doing it and seeing it happen yourself.”

Junior Amina W. seemed downright enthralled by the experience. “One of our main aims when going to the DNA lab was discovering if some of us were in some way related,” she said. “Despite knowing all of us are in some way related due to the idea that we originated from one person, we were discovering if some of us had a mutation that came from one person who lived in the Middle East 60,000 years ago…We gained a greater understanding about gel electrophoresis, a process through which we categorize and inspect DNA by separating them, and how to use a centrifuge.” She was candid in her final analysis of the trip. “I’m not saying we’re all going to become scientists from one lab in 11th grade but we can’t dismiss the possibility. This trip instilled in me a hunger to know more about my genealogy and my history.”